We must make moral choices about how we relate to social media

Wednesday, October 21, 2020 at 9:08PM

Wednesday, October 21, 2020 at 9:08PM My newest article on ethics and social media has just been published by The Conversation. You can read it below.

We must make moral choices about how we relate to social media apps

Recently a South African radio show asked, “If you had to choose between your mobile phone and your pet, which would choose?” Think about that for a moment. Many callers responded they would choose their phone. I was shocked… But to be honest, I give more attention to my phone than to my beloved dogs!

Throughout history there have been discoveries that have changed society in unimaginable ways. Written language made it possible to communicate over space and time. The printing press, say historians, helped shape societies through the mass dissemination of ideas. New modes of transport radically transformed social norms by bringing people into contact with new cultures.

Yet these pale in comparison to how the internet is shaping, and misshaping, our individual and social identities. I remember the first time I heard a teenager speaking with an American accent and discovered she’d never been out of South Africa but picked up her accent from watching YouTube. We shape our technologies, but they also shape us.

The potentially negative impacts of social media have again been highlighted by The Social Dilemma on Netflix. The documentary, which Facebook has slammed as sensational and unfair, shows how dominant and largely unregulated social media companies manipulate users by harvesting personal data, while using algorithms to push information and ads that can lead to social media addiction – and dangerous anti-social behaviour. Among others, the show makes an example of the conspiracy theory QAnon, which is increasingly targeting Africans.

Despite its flaws, the doccie got me wondering what our relationship should be to social media? As an ethics professor, I’ve come to realise that we must make moral choices about how we relate to our technologies. This requires an honest evaluation of our needs and weaknesses, and a clear understanding of the intentions of these platforms.

Tug-of-war with technology

Yuval Noah Harari, author of Sapiens, contends it’s our ability to inhabit “fiction” that differentiates humans. He claims you “could never convince a monkey to give you a banana by promising him limitless bananas after death in monkey heaven”. Humans have a capacity to believe in things we cannot see – which changes things that do exist. Ideas like prejudice and hatred, for example, are powerful enough to cause wars that displace thousands.

The wall between Israel and Palestine was conceived in people’s minds before being transformed into bricks and barbed wire. Philosopher Oliver Razac’s book Barbed Wire: A political history traces how this razor-sharp technology has been deployed from farms that displaced indigenous peoples to the trenches of World War I and the prisons of contemporary democracies.

Technology is in a constant psychological, political and economic tug-of-war with humanity. Yet, some of today’s technologies are much more subtle than barbed wire. They are deeply integrated into our lives – they know us better than we know ourselves.

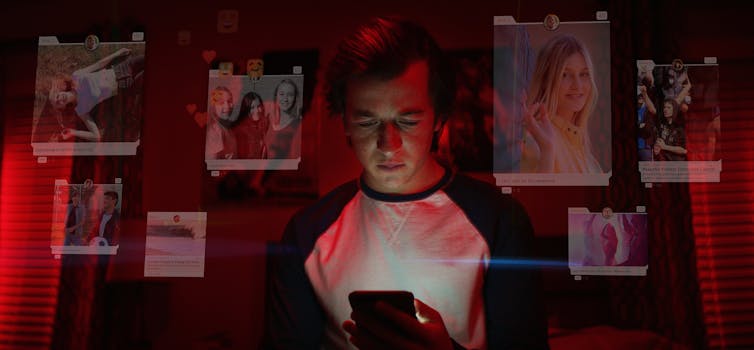

I have thousands of ‘friends’ on social media – far too many to relate to meaningfully. Yet, at times I can be more present to people that I have never met than I am to my family. This is not by chance – social media platforms are designed to seek and hold our attention. They are businesses, intent on making money. Harvard University professor Shoshana Zuboff, who features in the documentary, explains in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism that social media “trades exclusively in human futures”.

We are the product

Zuboff says that social media platforms exploit our emotions and pre-cognate needs like belonging, recognition, acceptance and pleasure that are ‘hard wired’ into us to secure our survival.

Recognition relates to two of the primary functions of the brain, avoiding danger and finding ways to meet our basic survival needs (such as food or a mate to perpetuate our gene pool). These corporations, she says, are hiring the smartest engineers, social psychologists, behavioural economists and artists to hold our attention, while interspersing adverts between our videos, photos and status updates. They make money by offering a future that their advertisers will sell you.

Or, as former Google and Facebook employee Justin Rosenstein, says in The Social Dilemma:

Our attention is the product being sold to advertisers.

If our adult brains are so susceptible to this kind of manipulation, what effects are they having on the developing minds of children?

The documentary also reminds the viewer that social media has a more subtle and powerful influence on our lives – shaping our social and political realities.

Fake news and hate speech

The documentary uses an example from 2017 in which Facebook use is linked to violence that led to the displacement of close to 700,000 Rohingya persons in Myanmar. Something that doesn’t really exist (a social media platform) violently changed something that does exist (the safety of people). Facebook was a primary means of communication in Myanmar. New phones came with Facebook pre-installed. What users were unaware of was a ‘third person’ – Facebook’s algorithms – feeding information that included hate speech and fake news into their conversations. In Africa, similar reports have emerged from South Sudan and Zimbabwe.

Read more: Netflix's The Social Dilemma highlights the problem with social media, but what's the solution?

Another example used is the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which also played out in Africa, most notably in Nigeria and Kenya. Facebook user information was mined and sold to nefarious political actors. This information (like what people feared and what upset them) was used to spread misinformation and manipulate their voting decisions on important elections.

What to do about it?

So, what do we do? We can’t very well give up on social media completely, and I don’t think it is necessary. These technologies are already deeply intertwined with our daily lives. We cannot deny they have some value.

However, just like humans had to adapt to the responsible use of the printing press or long distance travel, we will need to be more intentional about how we relate to these new technologies. We can begin by cultivating healthier social media habits.

We should also develop a greater awareness of the aims of these companies and how they achieve them, while understanding how our information is being used. This will allow us to make some simple commitments that align our social media usage to our better values.![]()

Dion Forster, Head of Department, Systematic Theology and Ecclesiology, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.