I have the great privilege of working with a number of very successful people. I have had the immeasurable honor of working with some of the world's top scholars, ministry and mission leaders as well as titans of industry and sport.

I am often accused of being an eternal optimist - I don't mind! Perhaps I am a little too optimistic, but I have generally found that most people that I encounter are sincere, well meaning, having a genuine desire to do well for themselves without harming others. This has been my experience with most of the people I have met at various levels of success in society.

Some generally observable traits in highly successful people:

Of course there are some traits that set the very successful aside from marginally successful or less successful persons. Among those traits I have observed such things as:

- A willingness to work harder than others.

- A measure of courage that is greater than the norm (some call this an appetite for risk).

- A singular focus and commitment in spite of adversity and opposition.

- Some exceptional skill or ability (whether it is business acumen, the ability to manage people or resources, or an above average ability in sport). Let me just say on this point that this has been much less important in the overall balance of success than I had initially considered. Determination, hard work and courage are certainly more important than 'giftedness'. I have met many average persons who have achieved exceptional things through sheer determination, hard work and risk.

Then there are some additional elements that I have seen that help in achieving success. These include:

- Confidence.

- Above average communication skills.

- Very good people skills.

- A network of strong and supportive relationships.

However, for some time I have been looking out for one additional trait - I first became aware of it some years ago when working with a Bishop who had an incredibly loyal following of clergy and members. He was courageous beyond measure, worked incredibly hard and had a clear and strong focus of social transformation and human rights. However, there was an additional element that I observed in his personality. Because I have seen that element in my own personality, and now observed it in his, I started looking for it in others.

What is a psychopath?

The condition that I am referring to is a mild form of psychopathic tendency. Psychopaths are characterized as having a strong lack of empathy, which is often expressed in amoral or antisocial behavior.

For example, when the average person sees a scene of murder or physical abuse they will experience a negative emotion. Something inside of them empathizes with the victims of the murder or abuse and so they distance themselves from the experience. The observer feels something of the pain, struggle and fear of the victim and the negative emotion that results causes a change in behavior.

So, for example, most people will not beat a helpless animal, a child, or an elderly person. Our ability to 'feel' what it must be like to be abused causes us to choose not to inflict such pain on others.

The psychopath, on the other hand, either feels no empathy, or has a reduced experience of empathy with the suffering of others. So for example studies have shown that psychopaths who inflict violence on women and children not only do not feel pain, disgust, or regret about their actions, in some severe cases the violent abuse actually causes their blood pressure to drop and their heart rate to slow. In other words the emotional response at violent abuse is so difficult to interpret that they wrongly associate the emotional response positively.

Now, let me be clear, that with the exception of truly violent criminals and political despots I don't think that there are many truly psychopathic individuals who achieve a great measure of success. They may achieve notoriety, but not success. Society, in general, does have a tendency to expose, restrain and even punish truly psychopathic individuals.

Mild psychopathic tendencies and success.

However, in its milder forms I am certain that there are some measure of psychopathic tendency in highly successful people. Why would I say this?

Well, I have seen that highly successful people often press ahead in spite of negative feedback, sometimes even from close friends or family. Moreover, they have a capacity to block out painful experiences and not allow the emotion of such an experience to slow them down, or at least stop them, from achieving their stated aims.

The simple reality, as my learned psychologist friend Philip Collier will tell us, is that all of us are regulated by our emotions. If we experience a positive emotion about something we tend to favor it and adjust our behavior accordingly. So, if you are good at something and people affirm your performance or behavior you tend to favor that activity. The converse is also true, if we experience a negative emotion associated with something (or someone) we tend to try to avoid that measure of 'pain'. There is a complex system of reward and aversion in the brain that is mainly associated with the hippocampus, the mesolimbic pathway, the mesocortical pathway which are primarily associated with the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine.

I wonder if you have seen the same thing in highly successful people? Take the olympic athlete for example. While others teenagers are responding to the promptings of their hormones on a Friday evening, dancing at nightclubs, eating at fast food restaurants and drinking alcoholic drinks with empty calories, the prize winning athlete is resting at home, having eaten a bland meal that contains the correct nutrition for training and performance. The athlete trains through the pain and even denies himself small pleasures for the sake of performance.

I have certainly seen the same traits among scholars who fill forego sleep (and even holidays) to get an article published, or authors who will spend years researching a new book. Of course there are many stereotypes in business of the successful business woman or business man who 'gets to the top' to find that they have lost their family and their friends, and perhaps even the true friendship and respect of their colleagues.

Something in them caused them to deny 'normal' emotional responses to conflict, desire, fatigue, hunger, and even love. As a result that they rose above what is common to most other persons. They ran faster, rode longer, worked harder, took greater risks, and achieved more.

As I have thought about it I have come to realize that it is far more complex than just writing off success to psychopathic tendencies. Of course there are those 'normal' persons who are coached and supported to greatness (I certainly spend a lot of time helping great people to achieve much more than they thought they could in business, and I know my friend Phil does the same of sports people).

But perhaps there are some persons who just have a little less connection with emotion, not so much that they become a danger to society and themselves, but just enough to rise above what is common to most people.

So, as always I would love to hear your feedback and thoughts! Do you think that this may be as common as I am suggesting? Do you have any examples of people (such as Richard Branson, Bill Gates, Warren Buffet - or others) that you could share?

Monday, February 27, 2023 at 9:45PM

Monday, February 27, 2023 at 9:45PM

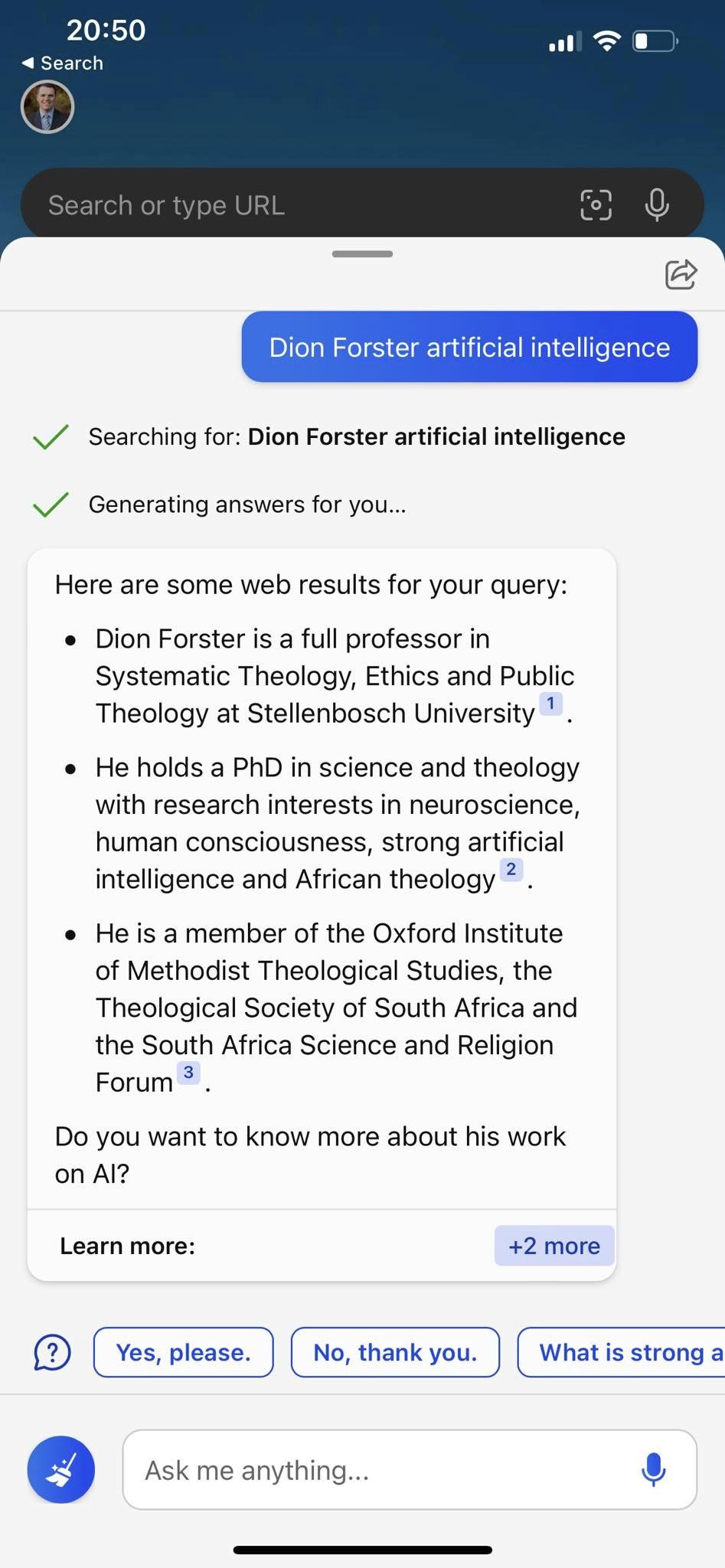

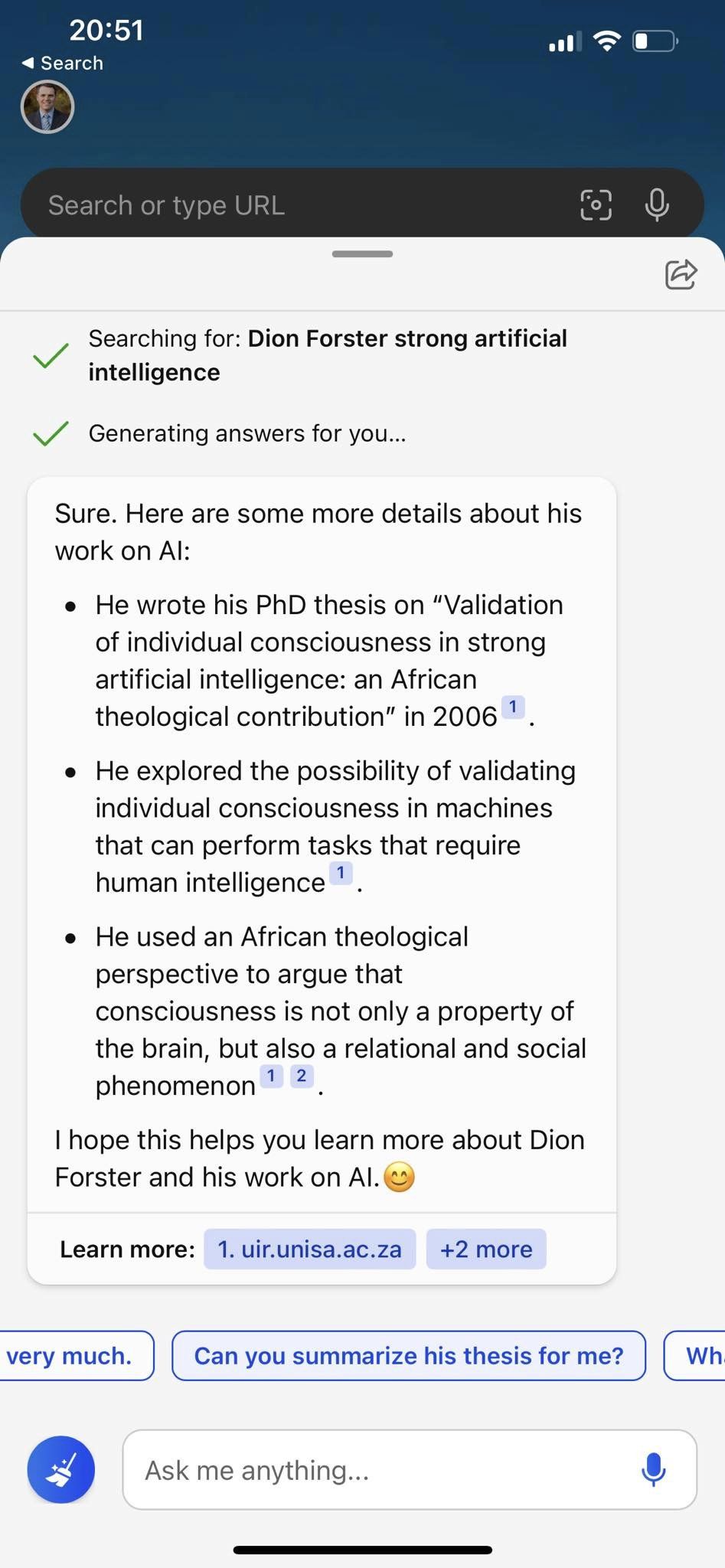

Prof Dion Forster

Prof Dion Forster  1 Comment tagged

1 Comment tagged  AI,

AI,  Artificial Intelligence,

Artificial Intelligence,  BingAI,

BingAI,  Phd,

Phd,  Strong AI,

Strong AI,  Theology,

Theology,  UNISA,

UNISA,  chatgpt,

chatgpt,  neuroscience,

neuroscience,  openAI,

openAI,  research

research