How you respond matters! What's happened a year after arriving in Amsterdam?

Tuesday, November 12, 2024 at 12:48PM

Tuesday, November 12, 2024 at 12:48PM - Witness to the truth

- Bind up the broken

- Live the alternative

- Replace evil with good

Tuesday, November 12, 2024 at 12:48PM

Tuesday, November 12, 2024 at 12:48PM  Wednesday, October 18, 2023 at 4:53PM

Wednesday, October 18, 2023 at 4:53PM There are some big changes coming! Please see the short video below for more details. We would appreciate your prayers.

Monday, February 27, 2023 at 9:45PM

Monday, February 27, 2023 at 9:45PM

Tuesday, September 13, 2022 at 9:56AM

Tuesday, September 13, 2022 at 9:56AM  On the 16th of August 2022 I was exceptionally grateful to deliver my Inaugural Lecture as a Full Professor at Stellenbosch University.

On the 16th of August 2022 I was exceptionally grateful to deliver my Inaugural Lecture as a Full Professor at Stellenbosch University.

The tradition of the Professorial Inaugural Lecture is that once one is promoted to Full Professor you have to make a 'profession'. It is generally assumed that some years or decades of research and scholarship will mean that you have something of meaning and value to say.

I took that very seriously. Wrestled for some months with what to 'profess'. Of course there was the pressure that the lecture's text had to be finalised in order to be prepared for publication! This was actually quite good - it meant that I had to read, listen, discern, and write! In the end I tried to discern what might be appropriate, fitting, and just for me to profess as a white, male, professor of Public Theology and Ethics in Stellenbosch South Africa in 2022? As it happened, the date that the University set for the lecture coincided with the 10th Anniverary of the Marikana massacre (about which I had done research and written previously). The mine workers who were shot in that terrible event had built their campaign around decency - what they were advocating for was a 'decent wage' (not just a 'living wage'). They wanted to earn enough to be able to undo the evils of colonialism and apartheid for them and their families. They were asking to earn enough to be able to undo the dehumanization of migrant labour, of inadequate education, of a lack of health care, and of ongoing poverty. They expected, that in a decent society they should be able to earn a decent wage. Sadly, 47 persons died indecently during that week's protests.

So in the end, the title of my lecture was:

Living more decently in an indecent world? The virtues and vices of a public theologian.

You can download PDF copy of the published lecture here.

The event was attended by family, friends, my wonderful colleagues, and members of the Rectorate of Stellenbosch University. It was such a special evening! I am so grateful.

You can watch the lecture itself here (or see the embedded youtube video below which will start playing at the start of the lecture itself, skip back to the beginning to watch the whole evening with inputs from special colleagues and friends).

Saturday, June 18, 2022 at 4:16PM

Saturday, June 18, 2022 at 4:16PM I was very grateful to deliver the 'Stellenbosch Unviersity Forum Lecture' on the 26th of March 2022.

This is the second time that I have been asked to deliver this prestigious lecture. I was very grateful to do so.

The topic of my lecture was 'A critical consideration of the relationship between African Christianities and American Evangelicalism: A cautionary tale of theo-political exceptionalism?' It is based on an article that I had published in the South African Baptist Journal of Theology that you can read here.

Thanks for your interest. While I feel, that by an large Christianity has made a positive contribution towards the care of persons in fields such as education, health care, political advocacy, and human rights, I do also think that it is important for us to name the ways in which religion in any form is harmful or dangerous.

I would love to hear your feedback or ideas on this topic!

Saturday, June 18, 2022 at 4:11PM

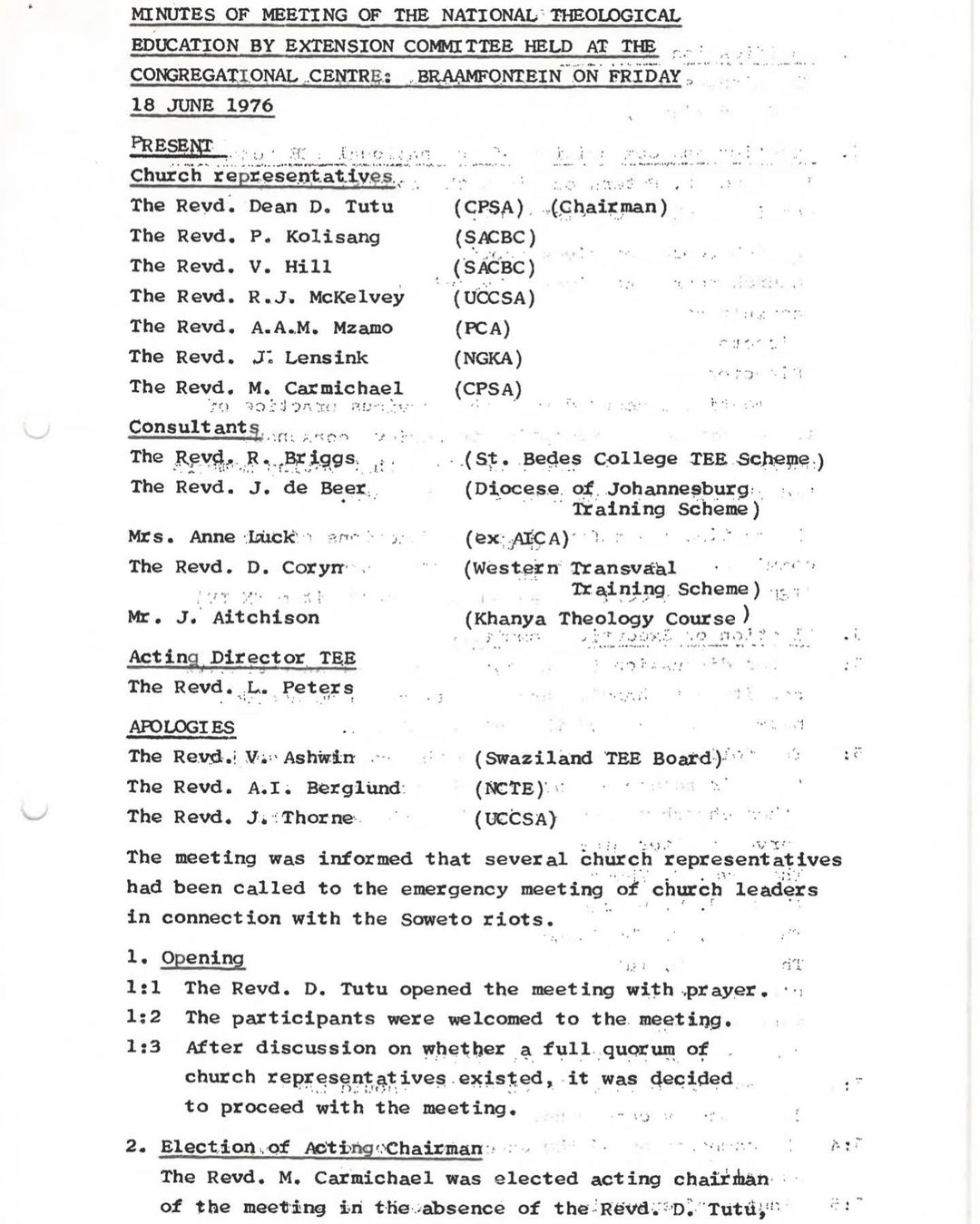

Saturday, June 18, 2022 at 4:11PM  Here is a bit of painful, and hopeful, history.

Here is a bit of painful, and hopeful, history.

Sunday, June 13, 2021 at 9:51PM

Sunday, June 13, 2021 at 9:51PM

I was recently asked to record an overview of my chapter ‘The nature of public theology’ from our new book, ‘African Public Theology’ (Agang, S; Hendriks, HJH; Forster, DA; Langham, 2020).

So, I decided to rework the video slightly and upload it here for anyone who has been looking for an introduction to public theology. This is intended to be an accessible presentation for newcomers, students, and persons who have some interest in the intersection between faith and public life.

You can find a copy of the book, ‘African Public Theology’ here: https://amzn.to/39nFgM5 Thanks for watching! As always, I would love to hear your comments, suggestions, ideas, feedback and questions!

Sunday, June 13, 2021 at 9:46PM

Sunday, June 13, 2021 at 9:46PM Why is it that in many western countries where “life expectancy” and “material well-being” have increased, “life satisfaction” is decreasing? German sociologist Hartmut Rosa suggests one reason is our “social acceleration.” In his book, Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World, he writes, “modern capitalist society, in order to culturally and structurally reproduce itself, to maintain its formative status quo, must forever be expanding, growing, and innovating, increasing production and consumption as well as options and opportunities for connection—in short: it must always be accelerating.”

One consequence is what Rosa identifies as the “three great crises of the present day: the environmental crisis, the crisis of democracy and the psychological crisis (as manifest, for example, in ever growing rates of burnout).”

Supporting Rosa, other research finds that socio-cultural unhappiness may be traced, ironically, back to the laudable values and beliefs of British, American, and European evangelicals.

In a 2020 article, Kyrkan och kampen för ett bättre samhälle [The Church and the Struggle for a Better Society], Swedish theologian Arne Rasmusson notes that dissenting nineteenth- and twentieth-century Protestants—including the Oberlin Colony, Quakers, Methodists, and Baptists—contributed to “the emergence and development of an independent civil society, democracy, religious freedom, and freedom of expression, the struggle against slavery, and the feminist movement.” As Marcia Pally argues (The New Evangelicals: Expanding the Vision of the Common Good), and as Rasmusson holds, this emerged from a mix of doctrinal convictions, political identity, and community structures, all of which supported dissent.

These communities did not submit themselves to religious and political authorities. They saw themselves as working towards a new religious, moral, and political order based on their conviction of God’s desire to save humanity from sin and its consequences. Each believer plays a part in this salvific work and must work out and live by moral principles in keeping with these religious convictions.

A second aspect of our story is found in The Quarterly Journal of Economics (February 2021). The article discusses the impact of an evangelical education and economic development program on poor Filipino households. Six months after the program ended, participants had “higher religiosity and income . . . and lower perceived relative economic status.” This suggests some correlation among certain forms of evangelicalism, economic development, and perceptions of dissatisfaction. Families who received both religious and economic training showed economic increases of up to 9% yet they perceived themselves as having dropped in economic status. Similarly, a 2017 research project in Germany found that, “relative to their Catholic counterparts, Protestants do appear to work longer hours” without, however, increases in wages. Protestants work harder but do not necessarily experience higher societal value or compensation.

These findings echo Max Weber’s argument in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, where he argues that under Protestantism, people develop higher motives for work. Weber notes that the Protestant Reformation, particularly Calvinism, created distrust in the Catholic Church’s ability to mediate salvation through its rituals. Thus, unsure of their salvation, all persons now had to live spiritually disciplined lives (while previously, only priests, nuns, and monks had to; the salvation of others was mediated through the Church). Insecurity about salvation and the effort to assure it became the basis for virtues such a diligence, thrift, and self-control.

Moreover, previously it was only religious functionaries who did ‘holy’ work. However, the Reformation taught that God is at work everywhere and all persons participate in God’s work. God feeds everyone, and the farmer participates by laboring to grow food. People thus began to attach moral and religious significance to work. They work harder, longer, and see their labor as virtuous merit to be admired and respected.

As Rasmusson’s and Pally’s work show, such values were deeply engrained in Protestant theology, identity, and practice. However, among dissenting Protestants, work became more important for the spiritual imperative of liberation. Not only a means of honoring God through economic production, work became a political tool to combat structural injustice such as poverty. Hard work and economic return, understood as available to all, create the conditions for a more just society. Work becomes associated with virtue, and the merits of hard work are understood as in the interests of the common good.

As dissenting Protestants moved from the societal margins to positions of social and moral influence, so did their values. The Protestant Ethic and the virtues of hard work (with capitalist rewards) became a subtle yet powerful ‘civil’ religion. Pally argues in Commonwealth and Covenant: Economics, Politics, and Theologies of Relationality that the same beliefs that led dissenting Protestant movements to liberate themselves from political and religious authoritarianism are the foundations for much of contemporary western political values. She writes “belief constitutes conduct” which in turn “constitutes belief.”

Michael Connoly, in The Evangelical-Capitalist Resonance Machine, echoes: much of contemporary economics is built upon a historical intermingling of “religious and economic doctrines” that were birthed in dissenting Protestant Christianities.

This leads us to the final part of our story, two new books on merit by Daniel Markovits and Michael J. Sandel. Markovits opens by saying that those who believe in the virtues of merit hold that “advantage should be earned through ability and effort rather than inherited alongside caste . . . social and economic rewards should track achievement rather than breeding.” Many in modern democracies might agree. Markovits continues, “meritocracy is now a basic tenet of civil religion in all advanced societies.” It is a civil religion since it operates as a largely unquestioned set of values and beliefs.

Yet, as we see in South Africa, where I live, and in many other countries, meritocracy may create its own problems. One is that often, many do not have access to the training that would allow them to succeed in a meritocracy. Markovits writes, “middle-class [and poor] children lose out to rich children at school, and middle-class adults lose out to elite graduates at work.” According to Sandel, the notion that people can better their lives if they “work hard and play by the rules” is no longer true.

Meritocracy is leading to deep social discontent and unhappiness among the middle and working classes. Those who lose out in the merit-race—because they were not groomed for it by their parents or by an (expensive) elite education—resent the economic and social elites for their privileged status.

Second a shift has taken place from working for the common good (as well as for one’s own betterment) to working only or mostly for one’s own economic and social privileges. Third, Markovits writes, elites at the upper echelons of income and power must work ever harder to protect their meritocratic privilege and status. Fourth, elite status is increasingly becoming a matter of inherited wealth, such that the meritocracy is no longer based on merit. Some end up in elite positions unsuited to them and must work exceedingly hard to maintain themselves there: “[m]eritocracy entices an anxious and inauthentic elite into a pitiless, lifelong contest to secure income and status through its own excessive industry.”

In The Tyranny of Merit, Sandel argues that meritocracy traps generations of workers in unsatisfactory work. Lack of education for merit-based work leaves working class persons with few choices about their jobs and often with two or more jobs to make ends meet. Economic and social elites, with economically rewarding and prestigious positions, frequently suffer the breakdown of family relationships, friendships, and their physical and mental health owing to stressful and demanding work.

Moreover, Sandel suggests, meritocracy damages society in changing the “terms of social recognition and esteem.” Working class persons feel undervalued and underrecognized; elites frequently begin to believe that their work makes them better than others.

Meritocracy, lack of access to it, and overwork from it seem to have trapped societies in immoral, unjust social systems. It is little wonder that many countries face negative “life satisfaction” indices. Perhaps the time has come to reconsider some of the unquestioned beliefs and values that form the foundations of our contemporary discontent. This would not be the first time that we have had to do this for the sake of a better future.

[This article was written by Dion Forster and was first published on 'Counterpoint Knowledge' on 17 February 2021].

Thursday, September 3, 2020 at 12:28PM

Thursday, September 3, 2020 at 12:28PM

Friday, July 24, 2020 at 2:09PM

Friday, July 24, 2020 at 2:09PM  Thursday, April 9, 2020 at 9:48AM

Thursday, April 9, 2020 at 9:48AM As we near the end of the 2nd week of strict ‘lockdown’ in South Africa in an attempt to curb the spread of the coronavirus, we have seen just about every possible social function going online! Virtual classes, virtual exercise sessions, virtual meetings - and of course, also virtual Churches! Or at least, Churches operating in digital spaces (Zoom, Facebook, YouTube, Microsoft Teams, Google Hangouts etc.)

Thanks for watching! As always, I would love to hear your comments, suggestions, ideas, feedback and questions!

Please subscribe and like the video!

You can follow me on:

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/DionAForster

Academia (research profile): https://sun.academia.edu/DionForster

Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/digitaldion

Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/digitaldion

Web: http://www.dionforster.com

Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/dionforster

Friday, December 20, 2019 at 8:39AM

Friday, December 20, 2019 at 8:39AM  From Mail & GuardianWealth is an unkind master. It owns us, when we think we own it, and it haunts and taunts us, when we do not have it.

From Mail & GuardianWealth is an unkind master. It owns us, when we think we own it, and it haunts and taunts us, when we do not have it.

I find it painful, and perplexing, that in such a deeply religious country, we live with such an unjust and systemically violent system. It runs counter to our morals and values for justice, care, and dignity. I wish we had the courage, and the creativity, to re-imagine our social and individual economic lives.

We need economic systems that serve our common good, not systems that enslave us, robbing us of dignity and fullness of life. Rampant free market capitalism is like a fire let loose in a forest. Without proper boundaries, it is not useful and constructive. It does not warm our bodies, cook our food, or sterilize our water. Rather, when left unchecked it will devour everything in its path and leave a wasteland of destruction.

South Africa, indeed South Africans, we have work to do. If you are a person of faith, particularly if you are one of the 86% of South Africans who indicated that you are Christian in the last General Household Survey, then I want invite you to pray with me, to ask difficult questions, to seek for solutions. We may not yet know what the answers are, but at least we can name what is wrong, and commit ourselves to find ways, in our daily lives, to replace evil with good.

We need a new economic and political imagination. You can read the article 'Why South Africa is the world's most unequal society' here. And, here is a short video that I made some years ago about Stellenbosch, the city in which the University at which I teach, is located. It is regarded as the most unequal city in the world.