The Indecency of the World Cup in Qatar—Making a F-ing Difference?

Tuesday, December 13, 2022 at 10:06AM

Tuesday, December 13, 2022 at 10:06AM  I love Berlin! It is an amazing city. I have been here many times in the last decade. As I write this, I am sitting in my office in the Theology Faculty at the Humboldt University Berlin, looking out over the Spree river towards the Berliner Dom (Lutheran Cathedral) and Museum Island. I am here on an extended stay as part of a research sabbatical. But, of course, there is another side to contemporary Berlin. It is a city whose residents challenge convention and push the boundaries. Graffiti is a common sight as are some rather interesting fashion choices.

I love Berlin! It is an amazing city. I have been here many times in the last decade. As I write this, I am sitting in my office in the Theology Faculty at the Humboldt University Berlin, looking out over the Spree river towards the Berliner Dom (Lutheran Cathedral) and Museum Island. I am here on an extended stay as part of a research sabbatical. But, of course, there is another side to contemporary Berlin. It is a city whose residents challenge convention and push the boundaries. Graffiti is a common sight as are some rather interesting fashion choices.

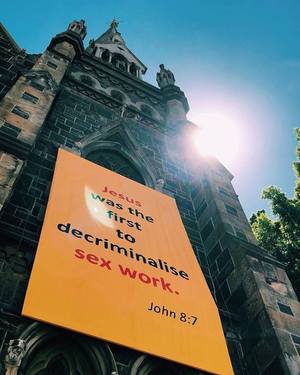

On my commute from home to the university, I cycled through a tunnel under the S-Bahn (elevated train) near Hackescher Markt, home to all the “cool” stores. Just as the Berliner Dom came into view, I was confronted by a mural by the “Football blackout for human rights” campaign that was pasted over the regular graffiti on the tunnel walls. It read:

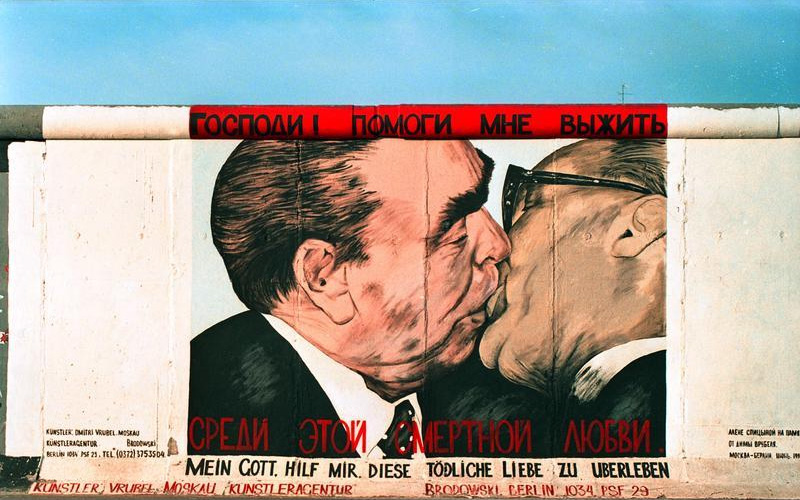

“On Dec 10, I’ll marathon-kiss my queer partner in public instead of watching football.”

I think the text is deliberately intended to shock the reader. It is somewhat reminiscent of the famous Berlin mural by Dmitri Vrubel, often referred to as the Fraternal Kiss. It was painted along the Berlin Wall at the East Side Gallery with the inscription, Mein Gott, hilf mir, diese tödliche Liebe zu überleben [My God, Help Me to Survive this Deadly Love]. The famous mural depicts Leonid Brezhnev (Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, 1960–1964 and 1977–1982) and Erich Honecker (head of East Germany under Soviet rule, 1971–1989) engaging in a fraternal kiss. The mural is based on a photograph by Régis Bossu, depicting the two communist leaders engaging in such a kiss in East Berlin on 7 October 1979. There is nothing strange about two men kissing. It is common in many cultures. But the mural elicited quite a stir. Some found it indecent and shocking, and it generated a great deal of public debate.

I am guessing that the artists behind the mural I passed are hoping to create similar discussion. Well, I sat down to write this piece, so it is working to some extent at least! Among the other slogans used by the “Football blackout for human rights” campaign are:

“Today I’d rather drunk-text my ex than watch football”

and “Today I’d rather masturbate all day than watching football.”

For me, the juxtaposition of what society deems “decent” (the Berliner Dom and the grand Museums) against the seemingly indecent slogans of the “Football blackout” campaign raised important questions about how we make sense of the world and construct our values. Let me explain why.

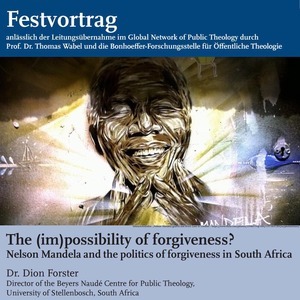

I started my sabbatical research in July 2022 by delivering one of the more important lectures of my career to date, my inaugural lecture as Professor of Public Theology and Ethics at Stellenbosch University (see, Counterpoint). In the lecture, I wrestled with “living more decently in an indecent world.” Since then, I have been speaking, teaching, and researching at some of the more “decent” Universities in Germany and the UK (Cambridge, Heidelberg, Bamberg, and Berlin). A lot of my conversations with students and colleagues have centered around the tension between the need for both decency and indecency in contemporary theology.

In my lecture, I was not advocating for a kind of “decent theology,” or “decency ethics.” I realize that what is presented as “decency” in some settings can be used to oppress sexual minorities, to stifle racial and ethnic diversity, or to “other” persons from non-dominant cultures.

Rather, I tried to imagine how a person might live a moral life, a good life, a life of greater justice that is directed towards the common good in the midst of many contemporary indecencies (such as poverty, racism, sexism, homophobia, and war). Moreover, I wanted to discern what we should do when these indecencies are held in place or strengthened by indecent systems and institutions, to the extent that—by means of economic, political, and religious systems—their actions and values, even in so-called “decent” societies have become indecent.

Consider the different treatment given to Syrian and Ukrainian refugees in Europe, or the religion that is used to oppress sexual minorities, or sport that is used to “purpose-wash” human rights abuses. We need a measure of decency to counter structural and systemic indecencies that humiliate and dehumanize people. The Israeli philosopher Avishai Margalit asserts that a “decent society is one whose institutions do not humiliate people.”

Though my focus then was on decency, I realize that we also need a measure of indecency to call into question some of what we have come to uncritically and unquestioningly present as “proper,” “acceptable,” and “justifiable” in contemporary politics, economics, and religion. I would characterize “oppressive decency” as a form of arbitrary, parochial narrow- mindedness.

To combat that, advocating for some measure of indecency in contemporary life is not without peril. Some groups may claim that their acts of racism, antisemitism, xenophobia, and homophobia further their version of what is good. In such instances we need to defer to greater decency—such as upholding our common humanity, fostering deep solidarity, and working courageously and tirelessly for universal justice. In short, we need to maintain a critical tension between both indecency and decency in our pursuit of the common good, and the lasting good.

So, my question is, what is the decent thing to do when encountering structural and systemic indecency in society? The decent thing to do may just be indecent by some contemporary standards.

The late Argentinian theologian Marcella Althaus-Reid suggested that in situations where systemic and structural oppression has been normalized, we need to develop an Indecent Theology that “troubles” some of these ossified and uncritically accepted “decent” beliefs and practices that lead to injustice and oppression. When her book was first published, it caused a major stir in “decent” theological circles. The South African queer theologians Hanzline Davids and Ashwin Thyssen argue that this “stir” is good as it “disrupts, transgresses, and erases stable binaries” such as heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, western supremacism, and the economic, political, and social systems that give these binaries the power to dominate and subjugate.

As I cycled away from the protest art in the S-Bahn tunnel, I was left wondering, for example, why I, and likely many other persons, have no moral problem watching the 2022 World Cup matches in Qatar, where there are indecent abuses of the human rights of LGBTQI+ persons, women, migrant workers, and many others. Yet, I feel morally challenged by an artwork advocating a “marathon queer-kissing session in public.”

The protest art helped me to realize that what I consider decent may in fact be indecent and that I needed a certain measure of indecency to help me to re-evaluate—literally to reconsider what I value or more pointedly re-evaluate what my values are based upon. Lisa Isherwood, the famous “body theologian” who uses our lived, embodied human experiences to think about God and relationship to God, wrote an appreciative (and critical) response to Althaus-Reid. Isherwood’s response is titled, Indecent Theology: What F-ing Difference Does It Make? She contends that indecent theology could help us to move towards a more honest, truth-telling theology.

So, I would like to invite you to dwell with those things that make you feel uncomfortable, that unsettle your sensibilities, that destabilize your social and historical values. What is it about them that makes you uncomfortable? What unquestioned values do they challenge? A bit of indecent theology might just be what is necessary to make a “f-ing difference” for the sake of a more decent world.

[I wrote this article for Counterpoint Knowledge. It was first published on 7 December 2022]