This week I had an article published in the online academic news service, The Conversation. The article considers why it took 200 years for the Methodist Church of Southern Africa to appoint their first woman Presiding Bishop. Moreover, in the same year that Bishop Purity Malinga was appointed as Presiding Bishop, four other women were appointed as regional (District) Bishops in the 6 nations of Southern Africa. Why did it take so long for a woman to be appointed to this position of leadership in the Church?

This week I had an article published in the online academic news service, The Conversation. The article considers why it took 200 years for the Methodist Church of Southern Africa to appoint their first woman Presiding Bishop. Moreover, in the same year that Bishop Purity Malinga was appointed as Presiding Bishop, four other women were appointed as regional (District) Bishops in the 6 nations of Southern Africa. Why did it take so long for a woman to be appointed to this position of leadership in the Church?

What does this mean for the future of Methodism, and indeed Christianity, in this region?

You can read the full article here: Methodist Church Southern Africa enters new era as women take up top positions

Methodist Church Southern Africa enters new era as women take up top positions

Purity Malinga, the new Presiding Bishop of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa. Supplied by Dion Forster, Stellenbosch University

Reverend Purity Malinga has just become the 100th Presiding Bishop to be elected by the Methodist Church of Southern Africa. She is the first woman in the church’s 200-year history to be elected to this position. As Rev Jennifer Samdaan, a prominent female minister in the church, points out,

There had been 99 men before her. For her to be chosen to lead us is wonderful.

The Rev Madika Sibeko noted in isiXhosa: “zajiki’izinto” (things are changing). Indeed, things are changing in the Methodist church.

The Methodist church is South Africa’s largest “mainline” Christian denomination, with its roots in the 18th century Wesleyan revival. Methodism quickly spread throughout Europe, the Americas, Asia and to Africa. In part this was because of the zeal of missionary societies, but also because of the spread of the British empire.

The Methodist Church of Southern Africa became an independent church in 1889. It is the largest Protestant Christian denomination in South Africa and has a predominantly black African membership.

Having a woman elected as the presiding bishop is of great significance to the denomination and the region. In this role Bishop Malinga will be the church’s most senior leader, with responsibility to guide the regional bishops and the ministry and mission of the church in the six southern African countries. These are South Africa, Namibia, Lesotho, Mozambique, Eswatini and Botswana. Her personality and inclusive style of leadership are likely to bring some important changes to the culture and identity of southern African Methodism.

She previously served as the first (and only) woman bishop of a regional synod, the Natal Coastal District (until 2008). She is a widely respected minister who first qualified as a teacher before entering the ministry and completing her theological studies at Harvard University in the US.

The Methodist Church of Southern Africa has a history of challenging tradition, and being at the forefront of working for justice and the rights of oppressed people. Among the other notable southern Africans who were Methodists are Chief Albert Luthuli, Africa’s first Nobel laureate; Nelson Mandela, another Nobel laureate and the first democratically elected president of South Africa, as well as Robert Sobukwe, the respected Africanist. Another prominent Methodist is Graça Machel, the Mozambican and South African women’s rights campaigner.

Bishop Malinga’s induction heralds a new era in southern African Methodism, and indeed church leadership in the region. Her election as the first woman to the post coincided with three other women being elected as regional bishops in the six countries that the church serves. These women are Bishop Yvette Moses (Cape of Good Hope District), Bishop Faith Whitby (Central District, the largest district, covering parts of the Gauteng and North West provinces), and Bishop Charmaine Morgan (Namibia).

The history

Methodism first landed on South African shores in 1795 cloaked in the guise of colonialism and the empire. This date was just four years after the death of John Wesley, the founder of the movement. This makes the Methodist Church of Southern Africa one of the oldest Methodist or Wesleyan churches in the world.

The first record of a Methodist in the region was in the Christian Magazine and Evangelical Repository (1802). The article tells of a British soldier named John Irwin who had been stationed at the Cape of Good Hope from 1795 to protect colonial interests in the region. It records that he hired a small room and began to hold prayer meetings and services.

The formal mission of the church began in 1816 under the leadership of Rev Barnabas Shaw. The Methodists of the Cape were entwined in colonialism, as were most missionary movements that emanated from Britain at the time. Nevertheless, they sought to minister not just to the colonisers, but to the indigenous people living in the area and to slaves.

This got them into trouble with the British colonial authorities. An example was the refusal by the governor of the Cape, Lord Charles Somerset, to let Rev Shaw establish a congregation at the Cape.

So began a history of civil disobedience. Rev Shaw’s response to Somerset’s refusal was blistering:

Having received this answer I therefore left His Excellency and determined to commence preaching without it. My resolution is also fixed never again to ask any mere man’s permission to preach the glorious Gospel.

The Methodist Church continued to show great courage in addressing social, political and structural injustice.

The church also failed in many instances. And there was often a gap between the ordinary members and local congregations, and the more progressive aims of the denomination’s leadership.

New era

It’s fair to ask why it’s taken almost 200 years for women to be elected to leadership positions in the church.

The most obvious reason is that Christianity in general remains a patriarchal religion. The Methodist Church of Southern Africa is no different: men dominate the leadership and formal structures at almost every level.

The church first allowed women ordination 43 years ago. By 2016 only 17% of the clergy were women, only 4% of regional leaders (circuit superintendents) were women, and there were no women bishops.

Some ascribe this to religious patriarchy, and others to the dominance of patriarchy in African cultures of the region. There have been women in senior leadership roles in other regions of the world where Methodism is present, such as the United Kingdom and the United States. However, in many contexts, such as Africa and parts of Latin America, the denomination has been less progressive in recognising and appointing women to senior leadership.

In her address to the 130th annual conference of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa at which her election was confirmed, Rev Malinga echoed the words of Oliver Tambo, the late anti-apartheid activist and leader of the African National Congress in exile, who said:

No country can boast of being free unless its women are free.

Her election, and those of Moses, Morgan and Whitby, bring South Africa a step closer to reaching that true freedom.

Dion Forster, Head of Department, Systematic Theology and Ecclesiology, Professor in Ethics and Public Theology, Director of the Beyers Naudé Centre for Public Theology, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, September 11, 2020 at 8:41AM

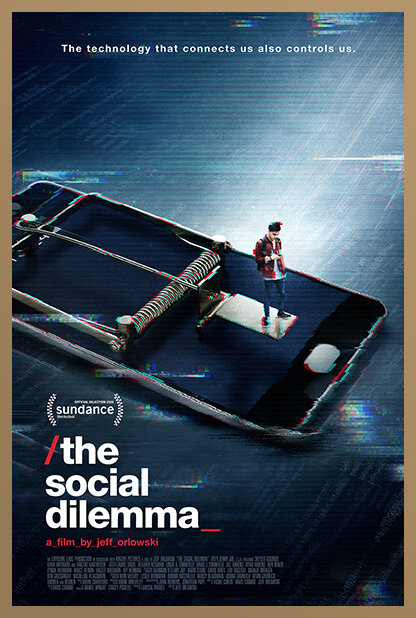

Friday, September 11, 2020 at 8:41AM  Last night our family sat down to watch the new Netflix documentary, 'The Social Dilemma'. It is well worth watching, and even more important to do so as a family!

Last night our family sat down to watch the new Netflix documentary, 'The Social Dilemma'. It is well worth watching, and even more important to do so as a family!