Dangerous echoes of the past as church and state move closer in South Africa

Tuesday, October 18, 2016 at 10:32PM

Tuesday, October 18, 2016 at 10:32PM Dangerous echoes of the past as church and state move closer in South Africa

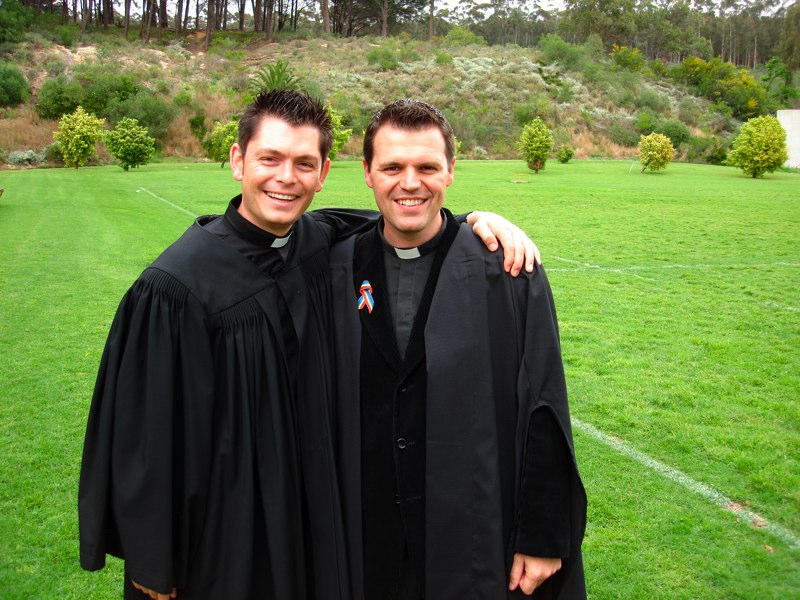

Dion Forster, Stellenbosch University

The Global Values Survey shows that religious organisations remain among the most trusted institutions in South African society. They enjoy higher levels of public trust than either the state or the private sector. This trust should not be abused or manipulated.

This is a challenge in most societies in the world. South Africa’s particular circumstances are complicated by a difficult historical relationship between the church and the state.

The state has often abused the church to garner votes and misinform, or to silence, its population. The church, on the other hand, has at times given moral and religious sanction that allowed the state to perpetrate significant injustices.

The issue of church and state relationships remains important for a number of reasons. First, South Africa is a deeply religious society. About 85% of its citizens are Christian, while a further 3% belong to other faiths.

Second, it has a clear precedent where an inappropriate relationship between the church and the state led to wide scale human rights abuses in the country’s apartheid past.

There appears to be a reemergence of the abuse of the trust that South Africans place in religions. This is a dangerous situation. An example is the governing ANC’s courting of the largest mainline denomination - the Methodist Church of Southern Africa.

When it does not find favour there, it reaches out to independent churches, which are the fastest growing religious groupings in the country.

The church and apartheid

The rise of apartheid politics in South Africa was inextricably linked to apartheid theology. It was the heretical theological views about how society should be structured, and whom God favoured, that gave the moral and religious sanction for a so-called “Christian” nation to perpetrate unimaginable human rights abuses.

At the turn of the 1900s the fledgling Afrikaners nation (Volk) developed a theology in which they viewed themselves as chosen by God for a particular task.

When the National Party came to power in 1948 they had the firm backing of the white Afrikaans churches. The churches – on the Nationalists’ behalf – used the bible and covenantal theology to construct a view that white Afrikaners had special rights at the expense of black South Africans, who according to the policy of apartheid, had none. Particular moral and religious values practised in the church and the home, became the laws of the nation.

Given the close relationship between the church and state, the moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church was jokingly referred to as the “second most powerful man in the country”, while the Dutch Reformed Church was referred to as the “National Party at prayer”.

This dangerous relationship detracted from the role of the state to protect the rights of all of its citizens, regardless of their faith. It also eroded the ministry of the church, which should hold the state accountable for its service to the people. The church also needs to be free to exercise its religious and moral mandate without political interference.

These religious and moral convictions separated people according to race and privileged a minority at the expense of the majority. We are still facing the consequences of those actions and choices.

Abusing public trust in religious institutions

Many gave a sigh of relief when the state and the church were disentangled at the end of the apartheid era. Sadly, that form of separation was short lived. Once again a governing party, in this ANC, is crossing that line.

Recently, Reverend Vukile Mehana, the ANC’s former chaplain general, defended President Jacob Zuma’s claim that people who voted for the ANC would go to heaven, while those who voted for other parties would go to hell.

Just before the 2014 elections Mehana, who is a very senior Methodist minister, encouraged pastors in Cape Town to solicit votes for the ANC, saying:

You cannot have church leaders that speak as if they are in opposition to government … God will liberate the people through this (ANC) government.

He would have done well to heed former Methodist Bishop, Peter Storey’s warning that:

the years since 1994 have surely persuaded us that democracy is not to be equated with the arrival of the reign of God.

So, how did this happen again? Of course there are many complex reasons that lead political parties to want the trust, and moral sanction, of large constituencies such as churches.

On the other hand, there are many church ministers and members who seek the power and opportunity that comes from being connected with political parties and party officials.

Mandela, the Methodists and unintended consequences

My 2014 research, showed that the path for the current abuses of church and state relationships came from former President Nelson Mandela’s relationship with his church.

It was not Mandela’s intention to co-opt the church, or abuse the trust that society places in religious institutions. But in a period in South African history when the narratives of reconciliation, forgiveness, hope and reconstruction were so central, he found a natural partner in the church for the project of rebuilding South Africa. He said:

Religious communities have a vital role to play in this regard [nation building]. Just as you took leading roles in the struggle against apartheid, so too you should be at the forefront of helping to deliver a better life to all our people. Among other things you are well placed to assist in building capacity within communities for effective delivery of a better life.

Mandela worked with faith leaders and church communities, and because he was viewed as a “good person” and a trusted leader, he won their confidence. Senior church leaders, such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu, worked alongside President Mandela in nation building initiatives.

The state also became accustomed to working with faith-based organisations, which in many poor and rural communities are important, and necessary, sources of support, development aid, and social identity.

But, as successive political leaders, and their political parties, came to power, their intentions seemed less honourable. Many outspoken activists and church leaders had been co-opted into senior government and party-political posts. And formerly trusted allies, such as Archbishop Desmond Tutu, started facing a backlash whenever they challenged political corruption or ineptitude.

And so, South Africa once again finds itself in a precarious position where a powerful and important social institution is being co-opted by political power. Political leaders are losing their religious and moral impartiality to serve the interests of particular churches and denominations at the expense of others. Political independence and religious freedom are once again under threat.

Of course there are many honourable religious politicians, independent and prophetic religious leaders. But, South Africans would be wise to heed the caution of motivational speaker Rob Bell:

A Christian should get very nervous when the flag and the Bible start holding hands. This is not a romance we want to encourage.

Dion Forster, Head of Department, Systematic Theology and Ecclesiology, Senior Lecturer in Ethics and Public Theology, Director of the Beyers Naudé Centre for Public Theology, Stellenbosch University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.